- Scroll down for video demonstration -

It’s all about ratio. In a world without ratio, notions such as love, beauty, fear, dissonance, wealth and distance would mean absolutely nothing. We are made of infinite combined fractions just like the world that surrounds us. We are a body of eternal numbers. The fact that we don’t know the number doesn't mean it is not there. Because we don’t know the numbers, we give names. When a note is played on an instrument, we hear an illusion. It seems that we’re hearing one sound but that sound is composed of an infinite number of notes called partials or overtones. The first overtone is double the frequency of the fundamental; the second is 3 times the fundamental and so on so forth forever. If we add up all these ratios, excluding the fundamental, we get the fundamental!

We gave the note Do one name because we heard one sound. If we heard the hundred tones that make up Do we would have called it a hundred names. We should be forever grateful to our super ears for making all those complex calculations for us and express-delivering a ready-to-use pitch to our minds.

Music is all about ratio. Let any pitch-producing material vibrate at a number of different frequencies and you get:

(1) a chord if all sounded at the same time,

(2) a melody if each sounded at different times.

During the latter, the ratios of sound to silence feel like rhythm and the ratios between the frequencies feel like harmony.

The oneness of rhythm and harmony is striking. If we maintain the same ratio between the various instances of a beat and apply enormous speed to it, it will transform inside our mind into a chord. The chord will have notes that are away from each other by the exact same proportions that were separating the beats in time.

A little back story

Many years ago I stumbled across a music history book that covered music from different parts of the world and I was mesmerized by the story of the Chinese emperor of the Zhou dynasty who sent out his court musician to the woods to bring back 5 bamboo pipes so they cut them and made a scale out of them. Five represented the five elements in nature, and according to the Chinese book of changes (aka “I Ching”), 3 represented heaven and 2 represented earth, and since harmony is the rapport of heaven and earth, they used the ratio of 3:2 to find the right notes. By cutting 5 bamboo pipes each to be 3/2 the length of the previous one, they ended up with 5 notes, each a fifth above the previous one. If these 5 notes are to be arranged in sequential order, they become what we call the pentatonic scale that constitutes the most characteristic sound of China and Japan.

Whether this is really the origin of the pentatonic scale or not, that story ignited a never-ending adventure in trying to understand the science behind the music and consequently changed the way I look at music. It was precisely what I needed to hear at a time where I had so many questions about topics that were generally considered obvious facts. For me, it was never a given fact that a major scale has 7 notes and an octave gets divided into 12. Why 7 and why 12? Why these 7 in particular and why this specific sequential order? What makes a melody beautiful and another boring? What makes a certain beat groovy when played by one drummer and the same exact copy of the beat flat when played by another drummer?

Beat is pitch in different time zones

One day I thought about this: Any musical note has a frequency and frequency is measured by Hertz (Hz) which is another way of saying “cycles per second”. When we say A = 440 Hz it means that when A is played on an instrument, the rate at which the air vibrates is 440 times per second. The eardrum picks up these vibrations and sends them in as one tone.

Given that pitch is all about the cycles per second it produces, any sound should, in theory, produce a pitch if we let it run at the same frequency. Take any sound you can think of, such as a spoon hitting a plate, a knock on the door or the sound of your sneeze, put it in an audio software and speed it up to 440 times per second and you will hear the note A. The reason for this is that when the space between the two sounds becomes extremely short, our ears stop hearing the spaces and start perceiving a continuous sound whose pitch is determined by the number of cycles per second these two sounds are oscillating at. This illusion is very much like in cinema where our eyes perceive the continuous motion of pictures once the frame rate is over 24 frames per second.

How would rhythm sound like at 50 times its original speed?

It's very simple. Fast forward one sound and you get a pitch, fast forward multiple sounds and you get multiple pitches. That's what I'll be showing in the video below. The video is self-explanatory but here are few written thoughts about the content for the curious humans:

The beat I’m using in this experiment is a simplified samba with one sound playing in groupings of 4, second sound playing in groupings of 3, the third playing in groupings of 2 and the fourth playing in groupings of 5.

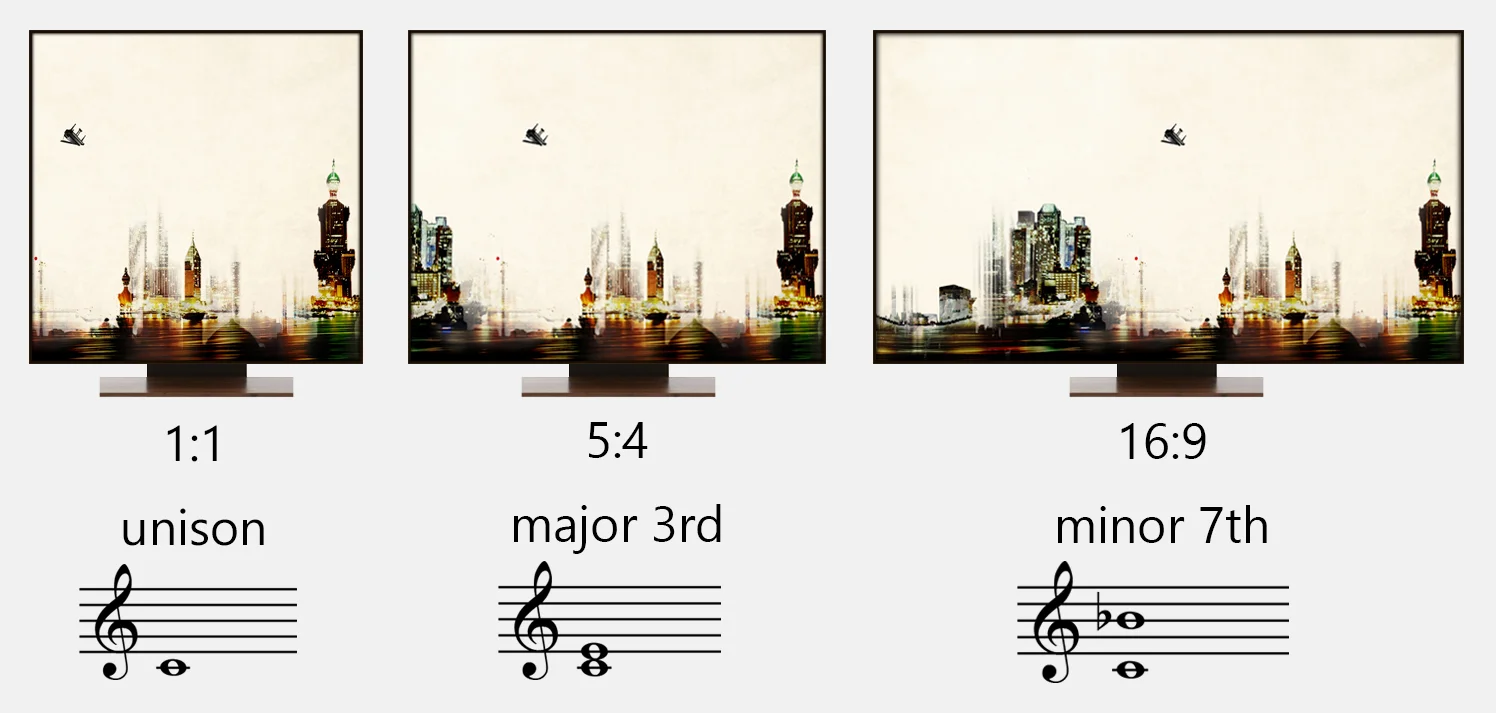

In acoustics, the frequency ratio of 1:1 of a note is the note itself, 2:1 is an octave, 3:2 is a fifth and 5:4 is a third. [ Ex: C x 1 = C; C x 2 = C (octave higher); C x 3:2 = G; C x 5:4 = E].

Note that there is the ratio and its reciprocal meaning that if 3:2 is a fifth above, 2:3 is a fourth below (intervals add up to 9 so inversion of 5th is 4th, inversion of 3rd is 6th, etc…).

Also note that dividing a frequency by 2 gives the same note an octave lower and multiplying by 2 gives an octave higher.

The experiment is run at 5168 bpm (beats per minute).

As 5168 bpm = 86.13 beats per second and as 86.13 Hz is the frequency of F, the sound which is playing the 4 groupings becomes that pitch. Consequently, the sound that is in groupings of 3 should become Bb since Bb is a fourth above F and a fourth has the ratio of 3:4 (we could also see this as a fifth divided by 2, ie 3:2 / 2).

The sound that is playing in groupings of 2 is double the sound that is playing in groupings of 4 so it will have the pitch F but one octave higher.

The sound playing the groupings of 5 will become the note Db since Db is a minor 6th above the low F and a major 3rd below the high F and a major 3rd in frequency has the ratio of 5:4.

Put F-Bb-Db-F above each other and you have the chord Bb minor.

Slow down

I will stop right here but not before leaving you with one final thought: Reverse all of the above!

If grooves become chords, chords should become grooves and this makes me wonder: How would a Count Basie Big Band chord sound like if slowed down 50 times? What about those Wynton Kelly chords on Kind of Blue? I did not go there yet so I'm still wondering but my feeling tells me that the resulting groove will swing and it will make you dance.

- Tarek Yamani

Credits:

Drawing by Luca Pearl

Find me on:

Twitter: http://twitter.com/tarek_yamani

Instagram: http://instagram.com/tarek_yamani

Facebook: http://facebook.com/tarekyamani

Soundcloud: http://soundcloud.com/tarekyamani

For Musicians:

A Melodic Approach to Mastering Polyrhythms in Jazz and other Groove-Based music in 56 steps: http://tarekyamani.com/dupletriple